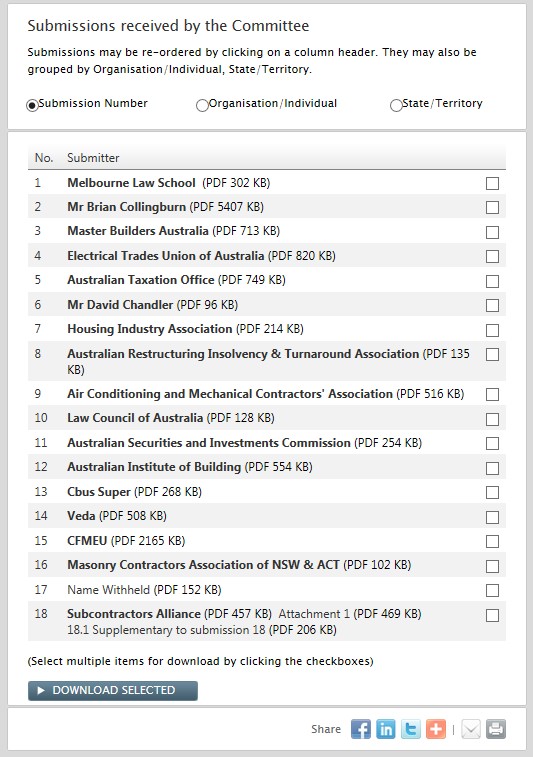

During the June 2015 hearing in Canberra of the Senate Economics References Committee’s inquiry into “Insolvency in the Australian construction industry”, Mr Dave Noonan, a national secretary in the Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union (CFMEU), listed what he thought were the main causes of business failure in the construction industry. In doing so he was drawing largely on figures published by the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC), which gathers that information from liquidators and other external administrators.

It’s the latest example of these ASIC statistics being quoted as if they were accurate and credible. In the CFMEU’s case, Mr Noonan took delight in agreeing with a Dorothy Dixer from a friend in the Senate (Senator Doug Cameron) that “the CFMEU was not named as one of the major reasons for corporate failure in the construction industry”. The inference was, of course, that the statistics proved that the CFMEU was not a problem for the industry.

What some of those who quote these ASIC statistics may not know is that the categories of causes from which external administrators must choose are predetermined. In other words, in nominating causes of failure external administrators must select from a list of categories created by the ASIC. Also, one of those categories – one which gets a large number of ticks – is labelled merely “Other”.

Furthermore, and curiously, the information given to the ASIC by external administrators appears, on the face of it, to be at odds with the widespread belief amongst the insolvency community, unions and regulators that many business failures, especially in the construction industry, are the result of fraudulent phoenix activity. Which raises the question of whether the number of permitted categories of causes need to be increased, and/or whether the categories need to be modernised, broadened and clarified.

Permitted categories of causes

The ASIC compiles its statistics on the causes of failure from information supplied by external administrators when they fill out their statutory reports online (Form EX01, Schedule B of ASIC Regulatory Guide 16). In filling out these reports – i.e., in nominating the causes of a particular corporate insolvency – external administrators must select from 13 categories of causes, which are shown below in the order established by the ASIC and using its exact words. This list of categories has existed for at least thirteen years. The only change since 2002 has been to alter the name of cause number 13, from “None of the above” to “Other, please specify”.

Select from these causes of failure

1. Under capitalisation

2. Poor financial control, including lack of records

3. Poor management of accounts receivable

4. Poor strategic management of business

5. Inadequate cash flow or high cash use

6. Poor economic conditions

7. Natural disaster

8. Fraud

9. DOCA (Deed of Company Arrangement) failed

10. Dispute among directors

11. Trading losses

12. Industry restructuring

13. Other, please specify

For those with business savvy, a rough definition of most of these ASIC categories can be deduced from their titles. (Which is just as well, because there is no official explanation.) But some categories – particularly “Fraud” (ASIC cause 8) – are vague and broad, and would benefit from the ASIC stating exactly what they mean.

Numbers for categories of ASIC causes

The ASIC’s latest report on this subject [1.] shows that in 2013-14 the “nominated causes of failure” – for all industry types, not just the construction industry – from highest to lowest, were:

Chart 1

| CAUSES OF FAILURE |

NUMBER

|

| Inadequate cash flow or high cash use |

4,031

|

| Poor strategic management of business |

3,975

|

| Trading losses |

3,078

|

| Poor financial control including lack of records |

2,908

|

| Other |

2,726

|

| Poor economic conditions |

2,312

|

| Dispute among directors |

1,743

|

| Poor management of accounts receivable |

1,017

|

| Dispute among directors |

271

|

| Industry restructuring |

222

|

| Fraud |

146

|

| Natural disaster |

122

|

| Deed of Company Arrangement failed |

55

|

| TOTAL |

22,606

|

Top nominated causes

An external administrator may nominate as many of the prescribed causes as he or she likes. According to the ASIC, external administrators nominated an average of between two and three causes of failure per report in 2013–14. So in its summary the ASIC highlights the top three nominated causes of failure for companies and provides figures on the percentage of reports by external administrator in which these nominated causes appear:

Chart 2

| CAUSES OF FAILURE |

2013-14

|

| Inadequate cash flow or high cash use (ASIC cause 5) |

in 42.6% of reports

|

| Poor strategic management of business (ASIC cause 4) |

in 42.0% of reports

|

| Trading losses (ASIC cause 11) |

in 32.5% of reports

|

These top three nominated causes have been the same for the past four years. It appears that “Other” (ASIC cause 13) may be a close fourth.

What is fraudulent phoenix activity?

The following explanation of phoenix activity comes from “Defining and Profiling Phoenix Activity”, a paper published in December 2014 as part of a research project (still going) by Associate Professor Helen Anderson, Professor Ann O’Connell, Professor Ian Ramsay, Associate Professor Michelle Welsh and Hannah Withers of the University of Melbourne Law School and the Monash Business School: [2.]

“The concept of phoenix activity broadly centres on the idea of a second company, often newly incorporated, arising from the ashes of its failed predecessor where the second company’s controllers and business are essentially the same. It is important to note that phoenix activity can be legal as well as illegal. Legal phoenix activity covers situations where the previous controllers start another similar business when their earlier entity fails in order to rescue its business. Illegal phoenix activity involves similar activities, but the intention is to exploit the corporate form to the detriment of unsecured creditors, including employees and tax authorities.

In a typical phoenix activity scenario, a company in financial difficulties, ‘Oldco’, is placed into liquidation or voluntary administration, or is simply left dormant (and may then be deregistered). Prior to this occurring, Oldco’s assets may be transferred either to a newly incorporated entity, ‘Newco’, or to an existing entity, such as a related company in a corporate group. “

Losses incurred

Estimates of losses incurred by the Taxation Office, employees, the Fair Entitlements Guarantee (FEG) scheme, sub-contractors, trade creditors , etc. as a result of phoenix activity vary, but are in the hundred of millions. On its website the ASIC quotes from figures in a report published by Fair Work Australia in 2012 which put the cost to the Australian economy at potentially more than $3 billion annually. The FWA report, “Phoenix activity: sizing the problem and matching solutions”, estimates that the annual cost of illegal phoenix activity is:

- up to $655 million for employees, in the form of unpaid wages and other entitlement

- up to $1.93 billion for businesses, as a result of phoenix companies not paying debts, and for goods and services that have been paid for but not provided, and

- up to $610 million for government revenue, mainly as a result of unpaid tax – but also due to payments made to employees under the General Employee Entitlements and Redundancy Scheme (GEERS) now the Fair Entitlement Guarantee (FEG). [3.]

Phoenix perpetrators and phoenix victims

A phoenix transaction carried out by a company normally brings about the end of the company. If the company’s former suppliers or subcontractors cannot survive without the payments they were receiving from the company, they too may have to close down. Hence, where phoenix activity is involved a failed company might be a phoenix perpetrator or a phoenix victim (or perhaps a phoenix perpetrator as a result of being a phoenix victim!).

For simplicity’s sake, this article will focus upon companies/directors that are phoenix perpetrators.

To which category of ASIC causes of failure do phoenixing events belong?

When looking at a failed company an external administrator might conclude that the company is a phoenix perpetrator (or, to describe the event more accurately, that the directors caused the company to carry out a phoenix arrangement). However, the predetermined list of causes which the ASIC has created doesn’t provide a category that is clearly made for such cases, or a category into which such cases might logically fit.

“Fraud” (ASIC cause 8) might be an appropriate category. But if the phoenix activity was “legal” [4.] it may not.

Even if “Fraud” is the cause category into which external administrators should, and do, put fraudulent or illegal phoenix cases, then it appears that the commonly accepted extent of such activity is not being reflected in their reports to the ASIC. As chart 1. shows, “Fraud” accounts for only 146 out of 22,606 causes.

Furthermore, anecdotal evidence suggests that “Fraud” is regarded by external administrators as referring to dishonesty by employees or outsiders – like the misappropriation of funds, or the abuse of position by employees, or wrongful or criminal deception by outsiders.

In a “legal phoenix” case the external administrator might select the cause category of “Other” (ASIC cause 13). The fact that this cause stands at an appreciable 2,726 out of 22,606 on the latest count (see chart 1.) adds weight to that possibility. But because the “please specify” descriptions that are requested and given in this category are not publicly disclosed by the ASIC (and probably not even analysed), we don’t know what is being included in this undefined, catch-all category.

In a “legal phoenix” case, and even in an “illegal phoenix” case, the external administrator might – for the purpose of reporting causes of failure – disregard the phoenix transaction, preferring the view that the company failed before implementation of the phoenix scheme as a result of other causes, such as “inadequate cash flow or high cash use”, “poor strategic management of business” and/or “poor financial control including lack of records”.

What we don’t know

There is so much we don’t know. For example:

- We don’t know whether phoenixing is generally regarded by external administrators as a cause of failure of companies.

- We don’t know how many phoenix cases – legal and illegal – external administrators encounter.

- We don’t know whether illegally phoenixing is generally regarded by external administrators as either an offence or “misconduct” to be reported to the ASIC.

Possible misconduct

The above discussion of causes has drawn on information supplied by external administrators in a particular section of the statutory report form EX01. However, the main reason for this form’s existence is to report, as required by the Corporations Act, possible offences that the external administrator has noticed.

In Schedule B external administrators are asked to advise whether they are reporting “possible misconduct”. It is possible, therefore, that reports of illegal phoenixing are contained in this main section of their reports.

But if this is so, the ASIC’s analysis of the statutory reports received – published in “Insolvency statistics: External administrators’ reports” – does not mention it. In fact, the word “phoenix” appears only once in the latest of those published reports, and then only in a passing manner. Perhaps this is to be expected, given that the word “phoenix” does not even appear in Schedules B and D nor in any other part of ASIC Regulatory Guide 16.

It’s possible that the word’s absence from the offences/misconduct section of the Regulatory Guide may be due to the fact that “there is no express ‘phoenix offence’”. [4.]

However, as “Defining and Profiling Phoenix Activity” explains, acts carried out during conduct of an “illegal phoenix scheme” are likely to be offences under one or more of several sections in the Corporations Act. Also, the acts are likely to breach provisions of the Tax Assessment Act, the Criminal Code Act and/or the Fair Work Act. [4.] .

Winding up

At this point we arrive at the same questions presented by the earlier analysis of the causes of failure. Is the phoenix activity observed by “the front-line investigators of insolvent corporations” [5.] being officially reported to the ASIC? If it is, how does the ASIC know it is, and how is the ASIC putting that information on the public record and before inquiries and researchers looking into phoenix activity?

Given the high level of interest in, and regulatory action to curb, the illegal phoenixing phenomenon, it is a pity that the store of the valuable knowledge derived from first-hand observations by external administrators is not being properly mined. The ASIC should give serious consideration to amending/expanding the Form EX01, Schedule B of Regulatory Guide 16 with simple changes to:

- include a category for corporate failures caused by phoenix schemes; and

- include a question in the misconduct section asking whether the company was involved in a phoenix scheme.

FOOTNOTES:

- Insolvency statistics: External administrators’ reports 1 July 2013-30 June 2014: Report 412, 29 September 2014

- http://law.unimelb.edu.au/cclsr/centre-activities/research/major-research-projects/regulating-fraudulent-phoenix-activity

- http://asic.gov.au/for-business/your-business/small-business/compliance-for-small-business/small-business-illegal-phoenix-activity/

- “Defining and Profiling Phoenix Activity”, December 2014, Associate Professor Helen Anderson and others.

- The ASIC often refers to external administrators as “the front-line investigators of insolvent corporations”. See for example, “Regulatory Guide 16: External administrations: Reporting and lodging”, para. R16.4

Previous posts on this blog regarding this inquiry: