Four senior representatives of the Australian Restructuring Insolvency and Turnaround Association (ARITA) (formerly (IPAA) gave evidence on 2 April 2014 at the public hearing held by the Senate Economics References Committee which is inquiring into the performance of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC).

Four senior representatives of the Australian Restructuring Insolvency and Turnaround Association (ARITA) (formerly (IPAA) gave evidence on 2 April 2014 at the public hearing held by the Senate Economics References Committee which is inquiring into the performance of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC).

Although the Senate is inquiring into ASIC, most of the questions faced by the ARITA representatives – and the sometimes lengthy discussions that followed – concerned insolvency administration, law and reconstruction, as well as the insolvency profession itself.

The following extract from the Hansard transcript provides insights into both ARITA’s current views on a range of issues to do with corporate insolvency and the kind of recommendations that the Senate committee might make.

I have split the transcript up by inserting the following subject headings:

-

ASIC AND ARITA WORKING TOGETHER

-

PROCESSING OFFENCE REPORTS (S.533 ETC) – FIRST DISCUSSION

-

ASIC AGENDA FOR INSOLVENCY

-

SPLITTING UP ASIC OR INTERNAL REFORM?

-

BUSINESS RESTRUCTURING: ADOPTING U.S. CHAPTER 11 METHOD

-

WHITE-COLLAR CRIME WITHIN THE INSOLVENCY PROFESSION (ARIFF ETC.)

-

STATUTORY REPORTS BY LIQUIDATORS REGARDING OFFENCES (S.533 ETC) – SECOND DISCUSSION

-

COMPLAINTS ABOUT INSOLVENCY PRACTITIONERS. STOP ORDERS.

-

PRE-PACK INSOLVENCY ADMINISTRATIONS

-

WHAT CHANGES IN THE LAW WOULD HELP ASIC PERFORM BETTER?

-

RENEWING A LIQUIDATOR’S LICENCE

-

LIQUIDATOR’S FEES FOR SMALL COMPANIES

-

DUTY OF CARE IN EXERCISING POWER OF SALE

-

ACCESS TO INFORMATION HELD BY ASIC

-

LIQUIDATORS LICENCES AND STOP ORDERS (AGAIN)

Appearing for ARITA were:

- David Lombe, President

- Michael McCann, Deputy President

- Michael Murray, Legal Director

- John Winter, Chief Executive Officer

The committee chairman is Senator Mark Bishop.

_________________________________________________________________

Extract from Hansard transcript of Senate Economics References Committee 2 April 2014

1. ASIC AND ARITA WORKING TOGETHER

CHAIR: I have some general questions. I think we might be going to explore four or five different issues and then my colleagues will jump in as appropriate. Firstly, do you consider that ASIC works effectively with your organisation?

Mr Lombe: In my view, the liaison side of the relationship has improved. I think, in the last two or three years, ASIC have been more active in consulting with ARITA. We have regular liaison meetings with them as a body. They have also, I think, ramped up their activity with senior practitioners, and there are regular meetings with them. In general terms, I think the liaison process is much better and that they are very much listening to some of the issues that are raised by ARITA and members.

2. PROCESSING OFFENCE REPORTS (S.533 ETC) – FIRST DISCUSSION

CHAIR: Do you draw any shortcomings to our attention?

Mr Lombe: One of the biggest issues that I would draw to your attention is that, in every administration, there is a form of offences report. In other words, if a liquidator, in reviewing the books and records or reviewing the conduct of the directors, forms a view that they have committed an offence under the act, they are required to make a report. In many cases, it is compulsory that they do that. The issue for us—and I believe it is a resources issue—is the fact that they are not being acted upon. That those reports are not being acted upon is a bit like the broken window in New York. I think there is a general perception within the business community that, if you do certain things at a certain level, there will be no effective review. We prepare thousands of reports each year and they are not being acted upon.

CHAIR: How do you know they are not being acted upon? Why do you assert that?

Mr Lombe: We simply get a letter saying, ‘There will be no action taken in relation to this matter.’ So it is very definite.

CHAIR: It is a standard form response?

Mr Lombe: Yes, it is.

CHAIR: There are always degrees of significance. Something can be a routine breach, an inadvertent breach or a breach that has no consequences, while something else can be quite deliberate, fraudulent and planned. What do you do with the second group when they say no action will be taken?

Mr Lombe: The difficulty that we have as official liquidators is that you get a matter off the court list and often that matter has no funds in it, so there are no available assets. Often that is a process by which directors have deliberately done that—it has been a deliberate course of action. If you report the matter to ASIC and there is no assistance from that space, there is not much you can do. If you felt really aggrieved by it or you felt that it was a matter that was of sufficient importance, you may be able to persuade a firm of solicitors to act on a pro bono basis, but that is very difficult. I found myself in that sort of situation with Babcock & Brown, where I had inadequate funds to be able to pursue a proper investigation. The only thing that was available to me was to ask creditors to fund me, which they did, which then allowed me to do a public examination, which brought out the conduct of directors and other stakeholders in that company. If you do not have funds in a matter, the courses are very limited….

3. ASIC AGENDA FOR INSOLVENCY

CHAIR: What needs to be higher on ASIC’s agenda?

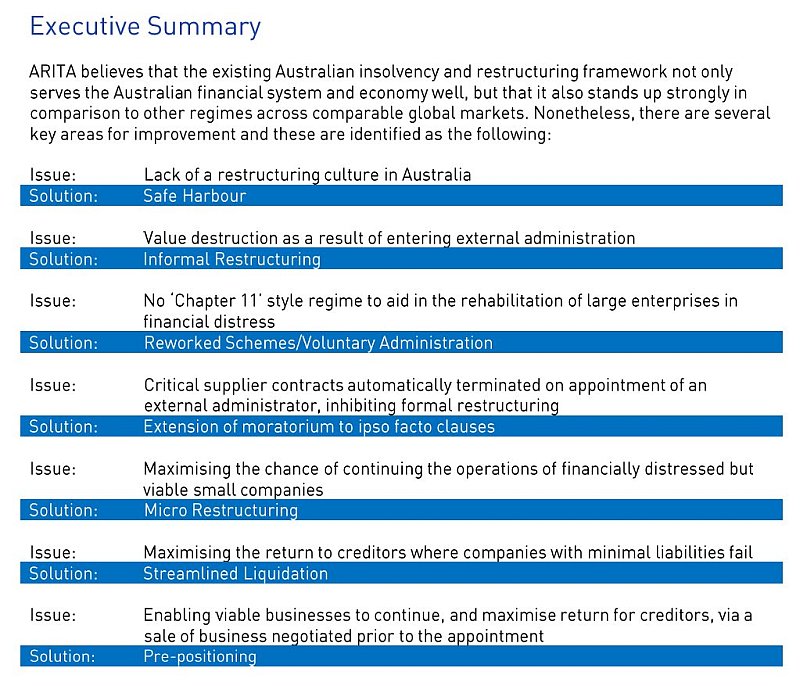

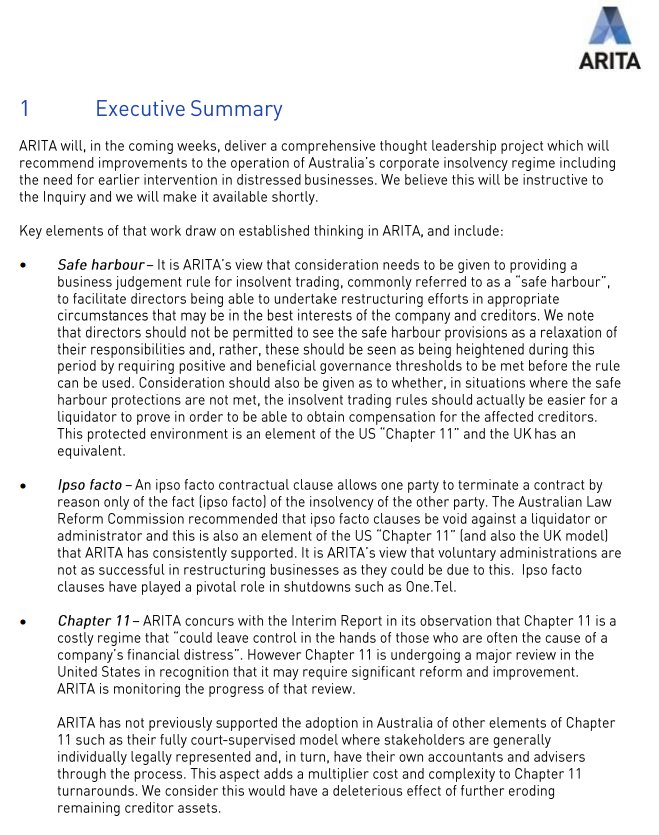

Mr Lombe: A reform package. There is the reform bill that is in parliament at the moment, but that is really in many ways at a lighter level. It is not a significant reform. It is harmonisation. It is giving more powers to creditors. But, importantly, it does not deal with, for example, a chapter 11 regime which might be considered. It does not deal with ipso facto clauses which may cause in an insolvency matter the liquidator or the voluntary administrator to lose the power to have a lease in respect of a store or a property, which then means that you cannot sell the business or restructure it. Prepacks are another item. There are a number of items that we have on our agenda for reform. I think it could be higher on ASIC’s list of things that they are looking at.

4. SPLITTING UP ASIC OR INTERNAL REFORM?

CHAIR: We had the discussion this morning—and I think you might have been in the back while we were having it—that over time ASIC has been given more and more responsibilities as the financial services industry has grown. Is there a case for splitting ASIC up or for internal reform of the organisation itself? Or is it just a resourcing issue?

Mr Lombe: From our perspective, it is not a splitting-up matter but a consolidation with AFSA, the regulator that controls bankruptcy. That was considered by the government previously and the ultimate result was that they decided not to move them together. With the economies of scale, I think I could see a better way of dealing with liquidators and trustees. At the moment they are two separate groups of people. But if you have a trustee he is more than likely a liquidator and vice versa. So I think there would be ways of making sure that, if you have an issue with, for example, a trustee’s conduct, that would be known to the regulator. Whereas at the moment there is a situation where potentially there could be an issue and it is not seen. Just in terms of dealing with liquidators and registered trustees, I can see some benefits to having one body.

5. BUSINESS RESTRUCTURING: ADOPTING U.S. CHAPTER 11 METHOD

CHAIR: Let’s turn to current insolvency laws in the context of the US chapter 11 processes. Is the current insolvency framework appropriate for restructuring a business in this country or is value destruction inevitable once an insolvency practitioner has been appointed?

Mr Lombe: That is a very big question.

CHAIR: It is.

Mr Lombe: What I would say to you is that our regimes work well. I am not sure whether you are aware of this but there was a paper called Safe harbour which talked about trying to allow businesses to be restructured without the value destruction. I think that particular issue got some discussion but it was very brief. I think we need to go back to that. In terms of chapter 11, again I do not want to mislead you. It is not necessarily a popular thing amongst insolvency practitioners. We very much have a wide church of insolvency practitioners that deal with smaller matters, medium-sized matters and larger matters.

CHAIR: Why is it not necessarily popular?

Mr Lombe: I think people have a view that it is a very expensive process. It is an American process. You are leaving the people who caused the problem in charge of the company still. What I would say to that is that we do not need to adopt holus-bolus the situation in the US. It could work effectively in Australia. I would refer you to a matter that I was involved in. The organisation was called United Medical Protection, which was a medical insurer who insured about 60 per cent of Australian doctors. Basically, medical services ceased at that particular point. In relation to that matter, it was a chapter 11 in Australia, being run by me as a provisional liquidator using the provisional liquidation regime and being carried out by a Supreme Court judge, Justice Austin. That was very much a situation where, effectively, for all intents and purposes you had a chapter 11 running in Australia. Chapter 11 is not for mum-and-dad grocery stores that go into liquidation.

CHAIR: No, it is not; it is for major enterprises.

Mr Lombe: It is for major enterprises. If you put a major enterprise into a VA the costs with the VA are probably going to approximate the costs if you had to go off to a court and talk to a judge. Often, it is advanced that a judge is not capable, or that our judges would not be able to do this. I do not agree with that assessment. I have found first hand, in dealing with Justice Austin, that our judges are very capable of dealing with it. In the US they have a separate bankruptcy court, but I do not believe that that is a major issue. I am a firm believer in chapter 11, but I might pass to one of my colleagues, Michael Murray, to give a little bit of background to that.

Mr Murray: As Mr Lombe said, chapter 11 is an arrangement whereby the restructuring of the company is left in the hands of the directors, or existing management, but under the control of a court. In Australia, we take a different approach where what we call the voluntary administration regime involves the appointment of an administrator or company liquidator to be in charge of the company—so in Australia the existing management does not have any further role in the restructuring of the company. There are pros and cons to each arrangement. In Australia it is commonly said that we do not have the same culture that they might have in America, in terms of attitudes to corporate failure, and that we would probably find it difficult, as Mr Lombe mentioned, to leave the management of the enterprise with the directors during the restructuring exercise.

CHAIR: But that is an indigenous concern. They leave the directors in control in the United States, and hundreds of companies have gone into liquidation over the years under chapter 11 and then traded out to be viable, ongoing concerns—all the auto companies, the airline companies. Just because there are some concerns in this country that, perhaps, the directors were not as competent as they could have been—the evidence from overseas is that that is not an issue. Why would it be different here?

Mr Lombe: I have a view—this is a personal view; it is not an ARITA view—that we are too obsessed with insolvent trading and with charging directors rather than saving jobs and saving businesses. You have given a number of quotations—

CHAIR: That is what this discussion is about: value creation and value destruction.

Mr Lombe: Exactly. There is no doubt that if you appoint a voluntary administrator, you appoint a receiver, you appoint a liquidator, there is value destruction. There is no doubt about that. Chapter 11 has a different connotation, which is why I am, personally, in favour of it. But, as I say to you, it is not necessarily a popular view.

CHAIR: No. I hear that loud and clear, but what I am pressing down on is: so what if it is not a popular view? If hundreds of companies have been saved to be now effective, viable concerns returning dividends to shareholders and employing tens of thousands of people, who cares if people in this country are upset?

Mr Lombe: These things need to be debated more. They need to be discussed. I was extremely disappointed that that safe harbour document just disappeared without being properly publicly debated.

CHAIR: Mr Murray, I interrupted you

Mr Murray: I was going to follow up on the point that Mr Lombe raised about the insolvent-trading laws in Australia, which are regarded internationally as quite severe. They are seen as an impediment to flexibility of restructuring, and the issue of value destruction comes up in that context. There is seen to be too much of a readiness to go into a formal insolvency arrangement where a more informal or more flexible arrangement might serve a better purpose.

CHAIR: So is there a bit of value in having a significant public debate around this issue?

Mr Lombe: I believe there is, and certainly for ARITA at the moment it is very much on the top of our agenda to come out with a piece of thought leadership which might encourage people to look at reform, because I think 1993 was the last serious reform we had, when the voluntary administration regime was brought in. We have been tinkering at the edges. There are some worthwhile things in the reform bill—I am not saying that there is not—but I think we should have that debate about substantial reform.

CHAIR: So your organisation is doing a fair bit of internal policy thought on the efficacy of an alternative situation, as opposed to a straight application of the insolvency laws and the immediate harm that flows from that.

Mr Lombe: Yes. Wherever I go as president of ARITA, I am making those sorts of statements—that we need to be looking at this. We need to be looking at reform. We need to have a dialogue about these sorts of matters.

CHAIR: Mr Medcraft, I think, said to us that the United States chapter 11 bankruptcy system is a very good structure. He believes it significantly mitigates the loss of value that results from essentially going in and just selling up whole entities and that it is far less harmful in terms of job losses and general destruction of value.

Mr Lombe: I would certainly agree with that part of his statement. I do not know about the rest of it, but I certainly agree with that.

CHAIR: There is some substance there on the table?

Mr Lombe: There is, yes. We would obviously like to encourage ASIC along those lines.

6. WHITE-COLLAR CRIME WITHIN THE INSOLVENCY PROFESSION (ARIFF ETC.)

CHAIR: ASIC has called for a review of penalties for white-collar crime. Do you have experience in white- collar crime within your professional organisations?

Senator WILLIAMS: I can give you some names: McVeigh, Macdonald, Patterson, Ariff. You need any more?

Mr Lombe: Are you alluding to Mr Ariff?

CHAIR: I am, by way of introduction. But more generally the question is: are current penalties and their application sufficient in the area of white-collar crime or do they need to be reviewed? That is really the issue.

Mr Lombe: Looking at the Ariff matter, to start off, that is a real blight on our profession. It is extremely regrettable and it is still a matter that gets a lot of discussion at the ARITA table. We are extremely embarrassed by it. The other thing that I would say is my view was the matter potentially was not handled as quickly as our profession would have liked. I think there were other ways. There is a thing called the Crimes Act which could have been looked at. Also, in terms of being an officer of the court, this matter could have been brought to the court. It could potentially have stopped him practising by having a receiver or some practitioner appointed to his practice to stop it, because I think it is the position that, whilst the investigation was going on and whilst the matter was proceeding in court, he was stealing funds. It is extremely regrettable and, as I say, it is a blight on our profession and we are extremely embarrassed by it.

But I would say this fellow was a criminal. He misappropriated moneys. We can sit down with a blank piece of paper and I can have a lawyer with me—the best lawyer in Australia—writing about how you stop people doing what Mr Ariff did, and the answer is you cannot because he is simply a criminal.

There may well be a case for better processes that make it easier to deal with these sorts of matters. I would say at the moment there are things in place which could have been accessed, but maybe there needs to be some reform to deal with this, to make it easier to deal with those sorts of things. I am not talking about someone who makes a mistake in their declaration of relationships, independence or indemnities. I am talking about someone who is taking money illegally, misappropriating money out of a matter. In that case, that has to be treated differently.

There are powers for ASIC to investigate those matters and get the material to understand that that is not a legitimate payment but a payment for a trip for his family, or things of that nature. From that perspective, I think there is some basis there. I might just ask Mike McCann, who is our vice president, to comment on that.

Mr McCann: The other day someone like Ariff was a criminal, and in a lot of cases of white-collar fraud or crime it is the directors of companies who are perpetrating similar crimes or other fraudulent activity, and they are true criminals.

In the case of Australia a lot of the penalties that we have seen handed out have been relatively modest compared to some of the high-water marks in the US et cetera, where they seem to have a much more rapid and much more draconian penalty regime. They seem to prosecute very quickly and the penalties are very severe. As a deterrent, I suspect that our penalty regime here is not quite sufficient, because there is a culture of crime and fraud being conducted around the country. While that is still the case in many countries, I think there could be more of a deterrent.

In our practice, obviously, we come across a lot of companies who have failed, for various reasons. To be honest, the majority are probably due to incompetence and misfortune, but there is certainly a hard-core element of fraudulent or criminal activity by people who have the status of directors of companies.

CHAIR: You said there is ‘core’ illegal activity.

Mr McCann: You do see on a recurring basis—not the same people necessarily—activity which is tantamount to fraud or criminal activity. You see that a lot in some these investment schemes that we are well aware of. That activity has been perpetrated very blatantly with the intention of taking funds from investors and similar parties. That is a criminal activity.

CHAIR: So you are saying to us that the penalty regime that applies is not an effective deterrent?

Mr McCann: Seemingly so, because we seem to have recurring activity of that sort of behaviour. People do go through that process. It takes them some time to be prosecuted and, if they are prosecuted, they serve a period. I am not sure if I am correct, but usually three to six years is a fairly serious sentence. I think in the US a lot of these crimes receive in excess of 10 years penal sentences.

Mr Lombe: Mr Chairman, could I make a small correction to what was said by the previous witness. It is on this topic. What it relates to is a comment that he made that ASIC had not pursued a criminal insolvent trading case for more than 10 years. I can tell the committee today that in fact they are pursing the Kleenmaid matter. It is a matter that is in Queensland. I think we are all familiar with the Kleenmaid product—washing machines, fridges and associated things. ASIC have taken criminal action against those directors and in fact a committal hearing finished this week and those directors have been committed to face trial.

7. STATUTORY REPORTS BY LIQUIDATORS REGARDING OFFENCES (S.533 ETC) – SECOND DISCUSSION

CHAIR: Thank you for that. Can we talk about statutory liquidator reports for a while? There is a huge volume filed every year—almost 7,000—from auditors and liquidators. We have had a submission from a number of firms that essentially says that auditors are frustrated with the statutory reporting process and that an enormous amount of time and expense is put into the preparation of such reports. They are filed with ASIC. There may well be some significant recommendations in their reports for follow-up action—drawing to attention shortcomings or deficiencies in various areas—and, by and large, they are received, noted, filed and moved on. In that light, does your organisation have concerns about the process and follow-up action deriving from the filing of the reports?

Mr Lombe: Yes. That was the issue I was talking about a little bit earlier—the extension reports. For example, in a liquidation by the court, you are required to lodge a section 533 report, which deals with offences committed by directors. What that means as a liquidator is you need to review the books and records, determine the transactions, try to find out what assets are there, look at insolvent trading and look at preference payments and all those sorts of things to understand what has gone on. We are required to file that report, and it does take time. So it is time and money, and often in these official liquidations there are no assets at all. If there are, creditors are effectively paying for that.

You are quite right: thousands of them are lodged and most of them come back ‘no further action’. I think it is frustrating to liquidators because they feel, ‘Why am I bothering to do it?’

The answer is, ‘You are required to do it under the law, so you need to do it.’ So we do not support anyone not lodging section 533 reports. But you can understand someone’s frustration, where they have reported offences and nothing happens.

CHAIR: The question then becomes: does ASIC use these thousands of reports it receives to effectively analyse and detect patterns of dubious behaviour?

Mr Lombe: I think you could probably say they have used them in the past to come up with a phoenix activity, so they have then had a focus on phoenix activity, and still do. I believe they are reading them for trends, but the frustration is that you are reporting an offence that you believe should be prosecuted in that particular company. So the fact that they are monitoring trends or things that are coming up is certainly useful, because it may mean that they see a trend and therefore they can take some action against it. But the fact that it is not being prosecuted is a frustration. I think sometimes that happens in larger matters as well.

CHAIR: So it is the lack of prosecutorial action that you complain of?

Mr Murray (?): I was just going to say at times, so do you use those reports where they have directors in a number of companies and they use that to identify a recurring activity for a particular individual or individuals, and then can you use that as a basis to seek a banning order, banning that party from being a director?

CHAIR: Let us get down to brass tacks. Does your organisation have a complaint about ASIC’s response to the reports once filed?

Mr Lombe: We have certainly raised this issue with ASIC, and the answer that comes back, in my recall, is that they simply do not have the resources to deal with it.

CHAIR: What is it that they do not have the resources to do?

Mr Lombe: To investigate the matters and prosecute the directors.

CHAIR: In its 2007 report, the ANAO looked at this issue and they found that, given the large number of reports received by ASIC each year that alleged offences against the Corporations Act, it was appropriate that ASIC had systems in place to prioritise its regulatory actions through risk scoring. It noted further:

… the small number of statutory reports subject to regulatory action by ASIC each year indicates that there is opportunity for greater regulatory action on these reports.

Are those findings from six or seven years ago relevant today?

Mr Lombe: I think they are very relevant.

CHAIR: In your view, could liquidators in their reports assist ASIC in distinguishing between the very serious breaches from the less-so? There are limited resources; there have to be priorities. Everything is not absolutely important. Is there a mechanism that could be developed whereby the industry advise ASIC that this set of issues or this set of complaints or this set of directors or this set of companies really are most egregious and need to be attended to?

Mr Lombe: I think that might be useful reform if that were the case. If there were some way of collating or rating, if you like, particular matters, I think that could be useful. At the moment the liquidator simply prepares his report and describes—

CHAIR: Perhaps you could develop a framework whereby, on a score of zero to 100, all of those above 80 points, for example—whatever the criteria are—are particularly egregious and warrant follow-up action, and the rest are therefore for analysis and noting purposes.

Mr Lombe: Yes.

CHAIR: Is it worthwhile giving consideration to the development of such a recommendation?

Mr Lombe: I think that would be worthwhile.

CHAIR: We are talking about developing criteria for risk scoring that liquidators and trustees would apply in the development of their report and provide to ASIC.

Mr Lombe: That is correct. If, for example, a bankrupt does something or does not cooperate, does not file his statement of affairs or whatever, his bankruptcy can be extended, so there is an actual penalty in those sorts of things. Whereas, in a liquidation, if there is a particular offence or whatever that does not get investigated then there is no penalty.

CHAIR: If that were the practice, after it were developed and became common practice, that would be a very, very up-to-date mechanism for noticing trends and behaviours and taking the appropriate either regulatory or prosecutorial action for the more severe cases.

Mr Lombe: That is right. Maybe in a situation where there are automatic offences, if you have done such and such, you cannot be a director for four years.

CHAIR: We will give consideration to such recommendations. Questions on this issue? Do you want to go onto the complaints about insolvency practitioners or do you want to go somewhere else?

8. COMPLAINTS ABOUT INSOLVENCY PRACTITIONERS. STOP ORDERS.

Senator WILLIAMS: Just about ASIC doing their job, Chair. We come to Mr Ariff and the frustration there with it being four years almost until ASIC acted. In this inquiry when I asked why it took three years to scrub out one particular financial planner when they had been given a file from the Commonwealth Bank. It is the speed at which ASIC acts that I have been finding frustrating when we know Ariff’s record and what he did.

In your submission you say that:

We mention that we support the IPA being given access to ASIC complaints details etc under the ILRB. The present laws do not allow ASIC to share information with IPA, nor IPA with ASIC.

That is the situation you were saying.

Mr Lombe: That is the situation except I would correct that we normally provide that information to ASIC.

Senator WILLIAMS: So you are saying you need more transparency between your organisation and ASIC to work on issues.

Mr Lombe: Definitely. For example, we might be looking at a particular complaint about a particular member. We might look at it and really struggle to see a lot wrong with it once we have gone through submissions and those sorts of things. But this same practitioner, for example, could be subject to a very serious ASIC investigation. We don’t know about that, so we are making a decision about a practitioner in isolation. That is the key point we are trying to make.

Senator WILLIAMS: While I have been running through this inquiry, Mr Lombe, I would like a stop order power be given to ASIC. In the case of financial planners, clear evidence is given to ASIC that they have given the wrong advice, have not done their job properly, ripped people off, done whatever—forgery, fraud, you name it. ASIC can just ring up that financial planner and say, ‘From this minute, you’re banned from operating as a financial planner. You can go to the AAT, if you wish to appeal it.’ How would you feel if that was also put on liquidators? If the liquidators were licensed instead of registered, so the licence was renewed every three years, and then ASIC could have gone to Ariff and in one phone call scrubbed him out. How would you feel about representing your organisation if that was to be put in place?

Mr Lombe: I think you need to have some form of investigation in relation to these matters because the nature of insolvency is there are confrontations and that can be—

Senator WILLIAMS: We had the 2010 Senate inquiry into liquidators and the previous government did draw up a white paper. I know the current government is working more to complete that. CarLovers are costing $1.8 million in legal fees to have Ariff removed. Who in administration has got a lazy $1.8 million to pay legal fees? That is outrageous.

Mr Lombe: Yes. I understand the point you are making. I think there needs to be a more streamlined position where there are serious issues of conduct. It needs to be easier or there needs to be a more streamlined process that works better to do that.

Senator WILLIAMS: Mr D’Aloisio told us at Senate estimates to deregister a liquidator is very difficult. If we have them licensed and ASIC have the power, it may never be used, but it puts your industry on notice that if you do do the wrong thing, one phone call and the next day you are down at Centrelink.

Mr Lombe: I would like to see a bit more than one phone call, frankly. I would like to see a proper process—

Senator WILLIAMS: The point I am making is I believe they should have the powers to say, ‘Right-o. We’ve got clear evidence here of wrongdoing,’ as they could have done with Singleton Earthmoving or Independent Powdercoating or whatever the companies were that were done over. But they haven’t got that power; instead, the company had to spend almost $2 million to have him removed out of one company. I think that is outrageous.

Mr Lombe: That is certainly wrong. I think there needs to be a more streamlined process; I agree with you—

Senator WILLIAMS: So do I.

Mr Lombe: where there is serious misconduct.

Senator WILLIAMS: There will be changes coming, I can assure you. I think you will be happy with them. I want ASIC feared. I want them to be a corporate watchdog where people are too scared to do the wrong thing. There is a lot of money out there, especially in superannuation, and there are people who do the wrong thing, clearly. I want to have a corporate watchdog that is feared out there in your industry or the financial planners or whoever to say: we do the wrong thing, ASIC will slam us straightaway.

Mr Lombe: We certainly do not support misconduct. As I mentioned before, we are very embarrassed by the Ariff matter and we certainly support a better process to deal with someone who has a serious allegation of misconduct against them.

Senator WILLIAMS: You saw the recommendations. The committee was chaired by former South Australian Labor senator Annette Hurley, and I thought it was a good inquiry. Mr Murray, was it you who said at first that we did not need the inquiry, or was it Ms North?

Mr Murray: It was not me; it was our previous president.

Senator WILLIAMS: So you think there should be closer work with ASIC in terms of transparency and sharing information with the organisation?

Mr Lombe: Yes, I would be very much in favour of that.

Senator WILLIAMS: That would be something you would like to see this committee recommend?

Mr Lombe: Yes, I would.

9. PRE-PACK INSOLVENCY ADMINISTRATIONS

Senator WILLIAMS: Is there anything else you would like to see? I agree with your pre-packs, by the way. I think that is something to really look at closely. I have done a lot of work with some liquidators about pre-packs to save the cost and return more money to their creditors; that is what it is all about.

Mr Lombe: It usually stops that destruction of value. Often you have got businesses with complex arrangements—leases, agreements, licensing and all that sort of stuff. As soon as you have an event of insolvency, they are void; they can be terminated. That is the difficulty in restructuring a business.

Senator WILLIAMS: The assets sold way below their value.

Mr Lombe: That can be the outcome. Often the reason that occurs is that you have had a destruction of value by the existing directors; they have traded the business down. By the time the liquidator, the voluntary administrator or the receiver gets appointed, the business has been seriously impacted by the trading.

10. WHAT CHANGES IN THE LAW WOULD HELP ASIC PERFORM BETTER?

Senator WILLIAMS: If you were in charge of Australia for one day, what changes would you make to our Corporations Law so that ASIC can perform their job better?

Mr Lombe: I would be trying to give ASIC some more resources, or have resources shifted, so that ASIC can focus on some of those key investigated aspects that I have been talking about today.

11. RENEWING A LIQUIDATOR’S LICENCE

Senator WILLIAMS: Do you support user pays?

Mr Lombe: One thing that has always amazed me in Australia is that I can go out today and set up a company and incur $1 million worth of a credit and I do not have to put any money down at all. I do not have to put a deposit down for creditors or whatever if the company gets liquidated. So I think there is some angle to that.

Senator WILLIAMS: I am referring more to when we license your industry. You pay a licence fee every three years. Perhaps when you apply for a licence you should have a face-to-face interview instead of something on paper. People can write anything about their character and good standing, and I think that needs to be addressed as well. But they are issues that we will address later.

Mr Lombe: One of the issues that was addressed in the reforms is that, if you want to become a liquidator, it is a paper driven exercise. If I want to become a liquidator, I have got some experience and some references and I give those to the regulator. I have never understood why there is not a face-to-face interview. The law is going to change if that bill comes in. When I became a trustee, I had to sit an exam and I had to sit through two hours of questions. So I think a face-to-face interview is the right thing in terms of when you initially get licensed. At the end of the day, it is probably something to consider in relation to ongoing licensing.

Senator WILLIAMS: I said to my eldest son, who is a chartered accountant, ‘Why didn’t you become a liquidator?’ and he said, ‘You’ve got to be joking!’ He really baulked at the idea.

Mr Lombe: A lot of people like the insolvency space because it is not merely liquidating companies but assisting companies to restructure. We do a lot of work to save companies from getting into liquidation and voluntary administration.

Senator WILLIAMS: If we can save the companies—whether it be pre-pack or chapter 11—we are saving the jobs. As the chair has said, a lot of creditors would not like the freezing of assets and payments et cetera. Case International is a big agricultural machinery manufacture right around the world. They were in serious trouble 15 years ago; now they are a prime player in agricultural machinery and those jobs have been saved.

Mr Lombe: I certainly support what you are saying and that is what our profession is developing into. The business acumen that our practitioners have is so important.

Mr Winter: In terms of the pathways into practice, from ARITA’s perspective we have an extensive education requirement which is effectively two units of Masters level study, which is delivered by Queensland University of technology. That is part of our requirement to become a member of ARITA. So, at a professional level, we are expecting a high standard, and of course you need to be a member of Chartered Accountants, CPA, or your relevant Law Society in order to gain membership of ARITA as well.

12. LIQUIDATOR’S FEES FOR SMALL COMPANIES

Senator WILLIAMS: It has been suggested to me that the liquidators’ fees should be capped when liquidating smaller companies. How do you feel about that?

Mr Lombe: I think that is something that should be investigated.

Senator WILLIAMS: Because 96 per cent of liquidations return less than 10c in the dollar to the creditors.

Mr Lombe: I think a capped fee situation is something that should be investigated. One of the things I would also say is that you might get a particular matter and there might be a capped fee on it, and then you look at it and you say, ‘There’s insolvent trading that I want to pursue and there are preference payments that I want to pursue,’ so in those situations you would have to go back to the creditors and say, ‘There are these things that need to be pursued,’ and the creditors would authorise you by increasing that cap. At the end of the day, creditors control liquidators and voluntary administrators being paid.

Senator WILLIAMS: They do to a certain extent. For example, KordaMentha, when they liquidated Ansett, were exempted, seven out of the 10 years, from reporting to ASIC. No-one should be exempted in the first year, so that ASIC can get a listing of the assets. It is ironic that during that period KordaMentha grew their offices right around Australia. We do not know how much they charged.

Mr Lombe: I do not think that is a political matter. I think it was an anomaly that existed then.

Senator WILLIAMS: I think there should have been three liquidators sent into Ansett—one for the aircraft, one for the real estate and one for the spare parts and machinery or whatever. It probably would have been over in two or three years instead of 10.

13. DUTY OF CARE IN EXERCISING POWER OF SALE

CHAIR: Can we now turn to section 420A of the act, ‘Controller’s duty of care in exercising power of sale’. It imposes a duty on the controller of a company, including liquidators, to take all reasonable care, when selling the property of a company, to obtain the best price that is reasonably obtainable, having regard to the circumstances when the property is sold. We have received a number of written complaints, and I think all of us have been lobbied extensively by persons who have been or are still aggrieved at a liquidation process. I have been made aware of allegations concerning hotels in Fremantle worth $2 million or $3 million sold off for $80,000 or

$100,000, without notice. A whole range of people have been to see me on those sorts of matters. The other example, of course, is the South Johnstone sugar mill case. The allegation is that it was sold at a much

undervalued asset price. That is the context in which I want to have a discussion about section 420A. How is this

section of the act enforced and what authority, if any, does ASIC have to deal with such allegations of assets being sold way under value?

Mr Lombe: Let me just start, and I might ask Michael Murray to help me a little bit on this question. Section

420A is a section which relates to the duties of receivers, so we are talking about receivers disposing of assets. Section 420A is very much a procedural-type issue. In other words, I get appointed to a hotel—

Senator WILLIAMS: Does that include liquidators as well?

Mr Lombe: No, it does not.

Senator WILLIAMS: Section 420A does not cover liquidators?

Mr Lombe: No. It covers receivers.

CHAIR: What is the difference between a receiver and a liquidator?

Mr Lombe: A receiver is appointed usually—unless it is a court-appointed receiver—pursuant to a fixed and floating charge. A liquidator is appointed by the court or via the voluntary administration process if no deed of company arrangement is put in place.

CHAIR: Are there similar or the same obligations in different sections on liquidators as there are on receivers?

Mr Lombe: They are different. Correct me if I am wrong, Michael, but my understanding of the liquidator’s duties is that he is not to act recklessly in the realisation of an asset. He does not have a section 420A but—

CHAIR: So you have got a lesser test.

Mr Lombe: A lesser test, yes.

CHAIR: Not to behave recklessly.

Mr Lombe: Yes. I think they are the right words, Michael?

Mr Murray: A liquidator has to act in the interests of creditors and, in acting in the interest of creditors, he properly should get market value or good value for the assets. But it is expressed more precisely in respect of receivers. To some extent, they are parallel, I think, or fairly equal.

CHAIR: But, whether it be receiver or liquidator, the allegation that is, repeatedly, assets are flogged off at way below their real value or market price if there was a contested market to acquire the particular asset. Does ASIC have any ability to get involved where such allegations are made. If not, why not?

Mr Lombe: Can I just make an initial statement in relation to 420A. I started talking about a procedural

section. What that means is that a receiver should look at the asset, he should go and obtain an evaluation in relation to the asset, he should make whatever inquiries he needs to make in respect of that asset to understand the nature of that asset, he should seek expert advice in relation to that asset if he needs to. He should do whatever he needs to do to understand that asset. He should then embark upon a selling process. Now, that selling process

would be one where he would instruct an appropriate agent. So, if you are selling a major hotel, then you are looking for a person who sells hotels, not someone who sells pubs. You would get someone of that nature, you would get expert advice as to how it should be realised and then you would kick off an appropriate advertising campaign. That might be eight weeks for expressions of interest, and there ought to be a staggered process of providing information to people et cetera. Then you would go through the process of obtaining the best offer. That would be one way of doing it. You could put it to auction, which would be another way of doing it.

So the idea of section 420A is to put in place a regime to ensure that you get the best price or a market price in relation to that asset. That is what it is trying to ensure. My understanding is that it is not in that section that ASIC can take action. Although you are obviously breaching the law, my understanding, again, is that it would need to be someone like a creditor or a director who says, ‘You’ve breached section 420A,’ and who would need to prosecute that through the courts. That is my understanding.

CHAIR: Or indeed the owner of the asset.

Mr Lombe: Yes, the owner of the asset. I do not think ASIC normally gets involved—

Mr Murray: Typically, it is the owner of the business that challenges the receiver on the sale of the asset, saying that it was sold at under its value. Correct me if I am wrong, Mr Lombe, but often owners of businesses have an unrealistic expectation of the value of their business, and it is not an uncommon complaint that what was a wonderful business was sold too cheaply, but that is not the reality.

Mr Lombe: I can give you an example of a major hotel—you would know the name; it is a hotel in Sydney. It was previously bought at $45 million. It was sold for around $20 million. This particular hotel was the subject of various programs on TV about the destruction in value that had occurred. In fact, the hotel, rather than having 200 guests in it—or 200 rooms multiplied by the number of guests—had three or four people in it. So you can destroy the value of particular assets. The reason I gave that example of a hotel is that the income a hotel can generate is about occupancy. If you have no income from that hotel, your price will be affected. In an insolvency situation, when you get appointed, that asset can be seriously distressed, and that is why the asset just will not be sold or will sell at a very low level.

CHAIR: Okay. I understand the point you are making about section 420A and the process that should be followed to realise maximum value when the assets are realised, and I also accept the point that Mr Murray made that often the owner of a business will have an inflated view of its value. Is there any recourse available to the owner of the asset or creditors both before and after the sale if they believe the asset has been significantly undervalued and flogged off at way below market price?

Mr Lombe: I think their recourse is to take legal action against the receiver for sale at below value.

CHAIR: And, essentially, alleged negligence, I suppose.

Mr Lombe: Well, it is alleged that they breached section 420A.

CHAIR: Is that the only avenue you are aware of?

Mr Murray: Yes, they can take court action. I would have to say, from my experience in reading the law reports, they do not often succeed—I say that as a generalisation. You asked whether ASIC has a power. ASIC has a power generally over receivers, which is under section 423 of the Corporations Act, in respect of misconduct or inattention to their duties, and there is a similar power in respect of liquidators. That is an overarching power that ASIC has in respect of the conduct of receivers.

CHAIR: Okay. Based on your experience, gentlemen, does this section 420A, as it applies to liquidators and receivers in the context of allegations of the sale of assets at way under market price, need to be strengthened in any respect or is it adequate?

Mr McCann: I think it is very adequate. As a practising receiver I know it is one of the things we are most mindful of whenever we take possession, say, for a bank of an asset and take it to market. We are very mindful of obtaining value and going through that process to ensure we are attaining the maximum possible price for the asset. That means we are very rigid around following a due process for the sale—in fact, to the point that, on day one of an appointment, you often get presented with people saying, ‘I want to buy that asset,’ and they put an offer on the table and you have to say, ‘That’s great. That looks like a very good offer but I cannot accept it because I have to go through a process to make sure that is the right value.’

CHAIR: Does due process in realising the value of the assets necessarily involve a public process and competition and tenders? If not, should it?

Mr Lombe: It does and it should.

CHAIR: I received complaints that business that have been wound up and the assets flogged off for way, way below market price was done by some fix where there was no tender process, and all of a sudden the new owner had it.

Mr Lombe: That is wrong.

Mr McCann: In the case of receivership that is clearly wrong.

CHAIR: Is it also illegal?

Mr Lombe: It is in breach of the law.

Mr McCann: However, in a case of liquidation there are circumstances where a liquidator with no funds has an asset and has no ability to trade or continue the business to allow an opportunity to achieve a higher value, if that is possible, and may need to act to close down the business and sell the assets, because there is no way that they can pay employees the next week or the next day because there are no funds available. In that case you will see a more rapid fire-sale type of situation.

Mr Lombe: It again goes to that issue of a liquidation versus a receivership.

14. ACCESS TO INFORMATION HELD BY ASIC

CHAIR: Yes, I get that point. You noted that ASIC receives and stores prescribed information under legislation and some of this information can be made public. But you argue that anonymous and aggregate statistics can be made public if ASIC so chooses. Can you put some more meat on those bones about why and how information should be made public?

Mr Murray: I think we are making the point there that Mr Harris made earlier about access to statistics. We feel frustrated—along with Mr Harris and other academics—about the lack of statistics, particularly in the insolvency area. We compare that very much, for example, to AFSA—the Australian Financial Security Authority, which is the bankruptcy regulator. They produce good statistics which inform the law reform process in bankruptcy. We do not have that sort of information in corporate insolvency. We were able to attend the previous session with Mr Harris, where you made a suggestion to him that he formulate some areas where ASIC might better produce information.

CHAIR: Could you take the question that I gave to Mr Harris and provide us, with some degree of urgency, a written note advising the type of information that ASIC has that should be made publicly available and that would be of use?

Mr Murray: Yes.

Mr Lombe: I would make you aware of a situation. ARITA gives a research prize so that someone can do research. One of our prize-winners was looking at deeds of company arrangement. When you go into voluntary administration, there is a decision about whether you go into liquidation or a deed of company arrangement. He was trying to work out how many companies go into deeds of company arrangement and how successful those deeds of company arrangements are. He wanted to get access to information from ASIC to be able to do that very important research. It would have cost thousands of dollars and ASIC just said, ‘We can’t give that information to you.’

CHAIR: Can’t or won’t?

Mr Lombe: Won’t.

CHAIR: Did they offer a reason?

Mr Murray: I think they said that they cannot—and I think this was referred to earlier—because they are legislatively prevented from waiving fees or giving out information.

CHAIR: Can you take that request on notice and provide us a written response?

Mr Lombe: Within the month?

CHAIR: Yes.

Mr Murray: Yes.

CHAIR: And also advise us if there are legislative prohibitions in the act that we need to have a look at as well in formulating our recommendations. If ASIC are prohibited under the law to provide the information, unless the act is changed, they cannot. So we need to be aware of that as well.

15. LIQUIDATORS LICENCES AND STOP ORDERS (AGAIN)

Mr Murray: I would like to make a final comment, please. Senator Williams, you mentioned earlier the issues about practitioner regulation and the cost of, for example, removing Mr Ariff from CarLovers and the cost to creditors, and also the idea of regulating a practitioner by way of ASIC immediately terminating their licence. I just wanted to point out—and I am sure you are aware—

Senator WILLIAMS: A stop order; not terminate their licence—put their licence on hold.

Mr Murray: I just wanted to point out that, following on from this report that we were involved in before, we have the bill and there is quite a regime in the bill giving powers to ASIC and also its counterpart AFSA in relation to those sorts of circumstances that you described. Also, in respect of removal of a practitioner, you do not have to go to court under the bill; the creditors can make that decision by—

Senator WILLIAMS: Has that bill has been introduced to the House?

Mr Murray: It is not in the House; it is what is called—

Senator WILLIAMS: It is being planned.

Mr Murray: It is an exposure draft and we have been working closely with Treasury with respect to refinements of its draft.

Senator WILLIAMS: I have looked over it piece by piece, the proposals, and have kept a close eye on it. Are you pretty happy with the proposals?

Mr Murray: We are—yes. We would like to think we have had a fair degree of input into it and we would encourage its further progress into parliament.

Senator WILLIAMS: Good. I have been briefed and I am very happy with what has been proposed.

Mr Murray: Thank you.

CHAIR: Thank you very much for your assistance today and for your involvement.

Mr Murray: Thank you.

______________________________________________________________________________

END OF POST

Four senior representatives of the Australian Restructuring Insolvency and Turnaround Association (ARITA) (formerly (IPAA) gave evidence on 2 April 2014 at the public hearing held by the Senate Economics References Committee which is inquiring into the performance of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC).

Four senior representatives of the Australian Restructuring Insolvency and Turnaround Association (ARITA) (formerly (IPAA) gave evidence on 2 April 2014 at the public hearing held by the Senate Economics References Committee which is inquiring into the performance of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC).