In a recent decision concerning liquidators of the Walton Construction group, Justice Robertson of the Full Court of the Australian Federal Court has determined that it would be inappropriate and against the law to take into account the insolvency practitioners’ Code of Professional Conduct.

In Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Franklin (liquidator), in the matter of Walton Constructions Pty Ltd [2014] FCAFC 85 (judgment 18 July 2014), His Honour said:

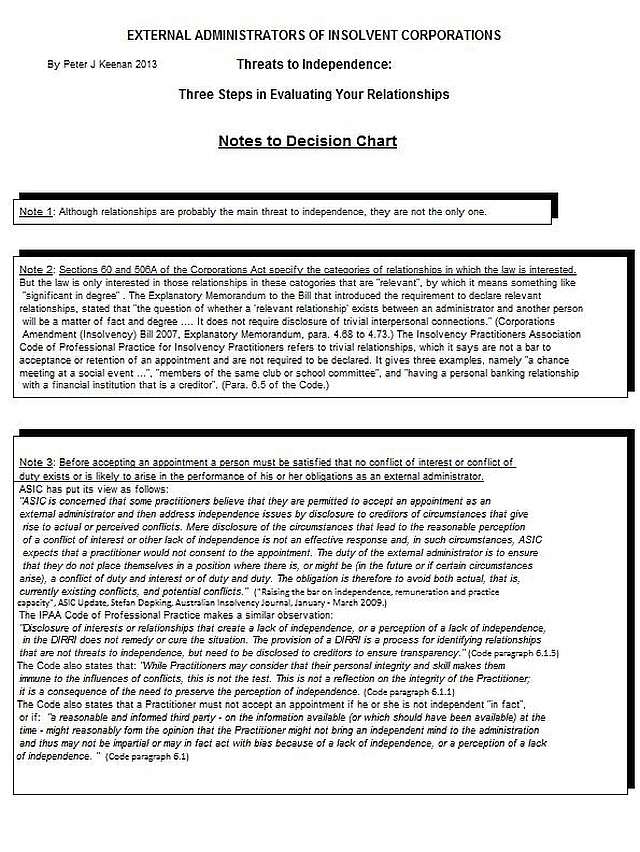

“I should add that I do not regard the Insolvency Practitioners Association of Australia’s guide entitled Code of Professional Practice for Insolvency Practitioners, on which ASIC relied, as extrinsic material appropriate or permitted to be taken into account in construing ss 60 and 436DA of the Corporations Act. To my mind, the general law would not permit that guide to be taken into account in construing those provisions and that guide is outside the scope of s 15AB of the Acts Interpretation Act 1901 (Cth). For example, the relevant parts of that guide were not reproduced or referred to in the explanatory memorandum to the Corporations Amendment (Insolvency) Bill 2007 (Cth). ” (Judgment paragraph 38.)

Conflict of interest

At the heart of the main decision in this case is the issue of conflict of interest and duty. I will analyse this part of the decision in a separate post. But here I want to discuss issues concerning compliance with and enforcement of the association’s Code of Professional Conduct.

An interesting predicament for ARITA

Justice Robertson’s comments are likely to cause something of a predicament for the association of insolvency practitioners, the Australian Restructuring Insolvency and Turnaround Association (ARITA). Naturally its Code of Professional Conduct (the Code) is binding on its members. So, it will probably review and amend this particular rule to bring it into line with the comments by Justice Robertson. Otherwise it would be imposing a requirement that the law does not acknowledge.

But, theoretically, it is not essential that ARITA bring its rules into line. If it thinks it necessary to have ethical rules that impose on its members duties greater than those imposed by the insolvency laws, it is entitled to do so. And it is entitled to take disciplinary action against members who breach such rules. Any member who doesn’t want to be bound by these extra duties can choose to resign from the association.

However it appears that enforcement of those rules by ARITA would be problematic. At the moment ARITA appears to enforce its rules only after a law enforcement agency (e.g. the Australian Securities and Investments Commission and the Companies Auditors and Liquidators Disciplinary Board) has made an unfavourable decision.

Apart from ARITA’s Code containing guidance as to what is meant by sections 60 and 436DA of the Corporations Act, ARITA has rules that impose greater duties and obligations than those imposed by the law. In constructing these extra duties and rules ARITA hopes that the courts will recognise them as a proper standard for judging the behaviour of insolvency practitioners and, by doing so, raise the standard of practice in the profession.

Until the comments by Justice Robertson in the Walton Constructions appeal case, it was widely believed that the statements and rules in ARITA’s Code applied not only to members of the association but effectively applied to all liquidators, because the courts would look to the Code when assessing whether the behaviour of a liquidator complied with his or her duties.

ARITA could suffer financially if this belief, based as it is on previous judgments by the courts, has been thrown into doubt by Justice Robertson. ARITA says that around 83% of all registered insolvency practitioners in Australia are ARITA members. But if its Code continues to impose standards that are more onerous than those imposed by the Corporations Act, and if the courts don’t continue to support its Code, more practitioners may choose not to join ARITA.

Comment by ARITA

Writing on behalf of the authors of the Code – the Australian Restructuring Insolvency & Turnaround Association (ARITA) – Michael Murray, Legal Director of ARITA, says:

“Interestingly, Justice Robertson said that he did not regard the ARITA Code of Professional Practice for Insolvency Practitioners, on which ASIC relied, as extrinsic material appropriate or permitted to be taken into account in construing ss 60 and 436DA of the Corporations Act. This was the case as a matter of law under the Acts Interpretation Act 1901 (Cth). As a matter of interpretation of the sections that comment is no doubt correct. But it continues to be the case that the Code is relied upon by the courts in assessing standards of practitioners’ conduct: Dean-Willcocks v Companies Auditors and Liquidators Disciplinary Board [2006] FCA 1438.”